The Mechanic Read online

Page 6

I was unaware of the four hundred political assassinations which shook the country’s confidence in ever again having stable government; and how could I have know, cuddling my teddy bear, that the French-Belgian military occupation of the Ruhr in 1923 would lead to strikes and hyperinflation which ruined everybody—except those clever or rich enough to have put their money into Switzerland or America?

No, I knew none of these things. But Adolf Hitler did. When I was four, he engineered a putsch in the Munich bierkeller—a lamentable failure which his propaganda minister eventually turned into a moment of high drama in the ascent of Nazism. Hitler was thrown into prison, but far from being his end, it was his beginning. Martyrdom suits some people. For Adolf Hitler, it was a creed written in the blood of millions.

My growing years, my schooling and my society were made as normal as possible by my increasingly anxious parents, despite the growing anger in the streets. I was a child when Wall Street collapsed, but by the time Germany was recovering, I’d already had my Bar Mitzvah, and Adolf Hitler was about to step into the shoes of Hindenburg and become the most powerful man in Germany.

What was it like to be a thirteen-year-old Jewish boy in Berlin when the SA was beating up the parents of your friends on the streets, and when Adolf was saying that every catastrophe of Germany was the fault of your people?

Who knew? I certainly didn’t. And neither did many of my friends. Because our parents shielded us. They met for dinner parties and derided the SA and the SS and the NSDAP as buffoons who would soon be thrown out of office as soon as Germany came to its senses. A second war? Nonsense. The Great Patriotic War was the war to end all wars. Everybody knew that. How could there possibly be another war when so many millions of young men had been slaughtered? When poisonous gasses had been used to blind and to maim? When monstrous and inhuman weapons like tanks had crushed bodies beneath their iron tracks and aeroplanes had flown over battlefields and dropped explosives from the sky? How could armies possibly fight armies, countries fight countries, when these weapons of evil were abroad?

How little we knew. What a fool’s paradise we lived in. I still remember the derision of my lawyer father when, in the privacy of our house, or in front of our friends, he was mimicking the goosesteps of the SS as they thundered down the streets of Munich and other cities in Bavaria.

‘Let them come to Berlin!’ he thundered like Bismarck. ‘We’ll show them the contempt in which we hold bully-boys and thugs.’

Today, I weep for my father’s ignorance. I despair now that I understand the enormity of his arrogance. Because of his, and the German Jews’ blindness, all European Jewry is dead.

Does that sound unusually harsh? Am I defaming the memory of the dead? Am I blaming my father, and millions like him, for what happened to me?

Looking back over the mountains of rubble which is the landscape of war, it’s all too easy to see the growth of Hitler’s insanity. In retrospect, it isn’t difficult to see where the concentration camps and the gas ovens and the Einsatzgruppen, the killing groups, came from.

But at the time, the evil seemed to creep over us all so slowly we accommodated to it as you slowly acclimatise to the winter, absorbed it into our daily routine, even ignored it. We got used to it as one gets used to a bad smell. We were constantly thinking that sanity would prevail, the smell would disappear as clean air blew in from beyond our borders.

And we had good grounds for so thinking. After all, at the end of June, 1934, Röhm and other top men of the SA were purged, along with most other high-profile opponents to Hitler. When we read of the purge, we all rejoiced. After all, it was Röhm and the SA who were the true evils, who organised the rallies. It was Röhm who had gathered together and controlled the vicious actions of millions and millions of unemployed men into the largest civilian army in history. And when Adolf Hitler stormed the hotel and had the leaders of the SA murdered, we thought that the Führer was reestablishing the laws of civilisation. No more beatings, no more rallies. The evil demon was dead. Germany was marshalling its resources for the Olympic Games. The loud-mouth Chancellor had come to his senses, got rid of the evil SA and now everything would be back to normal. The economy was starting to blossom. Women were again buying bows and ribbons. But this time from Aryan shopkeepers.

Prison Cells beneath the Palace of Justice

Nuremberg, Allied Occupied Germany

June, 1946

The months of isolation in the prison cell numbed his mind and made him wonder if he would ever be sane again. For over a year, he had been preparing in his mind for this denouement of his life. He was prepared for the accusations, the explanations, the verdict, the hanging. He had been a part of the machinery of death, and the moment the Reich collapsed, he had accepted that if caught, his life would be at an end. He’d been miraculously free for months before being captured by the Americans, rounded up because a concentration camp survivor had seen him queuing in the streets and informed the military. He’d even gone quietly; he’d not denied the allegations; he’d even cooperated with the Provost Marshal and filled in some of the details. Why deny it? The records were there. Denying would cause delay, and since the end of the war, he’d been waiting for a tap on the shoulder, a gun in the ribs. Yes, he’d only been a mechanic, but this was the era of allied retribution, and he was one of the operatives of the death camps, and he, like the others, would probably be brought to trial. How could he deny that he’d the mechanic who made the machinery of death work so efficiently? And when Germany lost, he was one of the guilty ones who would pay the price for Hitlermadness.

His wife knew it was coming, but his daughter, God bless her, didn’t know that her father would probably never see her grow up. She would miss Daddy, and then she’d get on with her life, trying to put together the broken bricks which one day would build the foundations of a new Germany. His family would miss him, mourn the cruelty of the war, curse Hitler and the Nazis, and survive. That was all they could hope for … survival.

But when his trial was suddenly truncated, and he suffered the tantalising … the excruciating … agony of waiting for the trial of his former colleagues to be over so his could begin afresh, it seemed as if the torments he had willed to dormancy suddenly erupted. He was riven with anxiety, so that at times, when he lay on his bunk, he found it almost impossible to breathe. Life now was so different from when he was a defendant with all the other defendants; then, he felt he was part of a group, and the group would be found guilty. Now he was on his own and he felt totally isolated and exposed.

Only the briefings with his lawyer seemed to offer him any relief. He had started off hating the arrogant and insufferable Broderick, but during the past month, this stiff and humourless American lawyer had become his link to the outside world. Even the guards didn’t talk to him anymore. They, like his former co-defendants, assumed that he had turned stool pigeon and was giving evidence to incriminate them so that he could save his neck.

Again the footsteps in the hall. Again his neck and underarms prickled at the anxiety of a guard throwing open the heavy iron door and barking out an order. It was lunchtime. He was usually called to a conference with Broderick at lunchtime, after the lawyer had spent the morning defending the others. A ten- to fifteen-minute series of barked questions about his activities during the war; evidence he’d already given to his first lawyer who’d been forced to return to America to attend his sick wife. But Broderick insisted on going through everything again. For the record. And as the days wore on, Wilhelm was forced to admit that he enjoyed their interviews. It made the day shorter.

But even though it was lunchtime, he hadn’t touched the slop pushed through the slit in his door. Hunger was a memory. He was losing weight, and he didn’t care. He could tell, because his trousers, once snug, were now baggy. But he had no appetite. Perhaps when he was found guilty and was hanging from the rope, he would weigh so little that it might gain him an extra couple of seconds of life …

‘On your fe

et, Deutch.’

The junior guard. New York accent. ‘Yer’ instead of ‘your.’ A pronounced ‘ai’ in the name ‘Deutch’, making it sound contemptuous. ‘Daitch’. Such anger from one so young. Did this young and innocent American Long Island boy, born and nurtured in safety and wealth, know anything about what had happened in Germany from 1923 until the advent of Adolf Hitler? What could a boy born in the wealth and security of America know of the fears of a Communist take- over, of the degradation suffered by all Germany with the imposition of the terms of the Versailles Treaty, or the enemy in the streets, or the collapse of money so that savings became worthless overnight and ruined entire families? What could a New Yorker know of the immorality of the women who prostituted themselves for silk stockings or cigarettes, or the invasion of Gypsies and homosexuals and Slavs and Jews taking up jobs and German manhood being unemployed … What could this rosy-cheeked guard know of any of the suffering he and his family had endured? Sure, the collapse of Wall Street had caused a depression and some stockbrokers had plunged to their deaths while a few American farmers had been kicked off their land. But they had a Messiah called Roosevelt; Germany’s Messiah was called Hitler. The difference was that one was victor, the other was vanquished.

‘On your fucking feet, Kraut,’ the young man shouted. Wilhelm got slowly to his feet. Lack of food meant that his head began to spin with the sudden exertion. He felt giddy and teetered to one side. The guard thought he was making an escape bid and snapped his rifle into the horizontal position. ‘Back away now!’ the boy shouted.

Wilhelm put up both his hands to assure the guard that it was illness, not intent which had made him totter to the left, but the guard raised the rifle to his eyes and cocked the trigger. One bullet, and it would all be over. A drunken lunge at the guard, and nothingness. Was it worth it?

‘Back away from the door now, Deutch, or I’ll shoot. Sarge!’ the frightened guard screamed suddenly. ‘Prisoner trying to escape! Sarge!’

More feet. Running. Wilhelm’s head was like a balloon filled with water. The events seemed to be disconnected from reality. Boots running in the hallway. Another man. Bigger, fatter. The sergeant. Revolver drawn like some Hollywood cowboy in a Western movie.

‘Over to the wall, Deutch. Move! Hands in the air. Now!’

‘You don’t understand. I’m sick.’ They didn’t speak German.

No compassion.

‘Move to the wall, Deutch. Right now or I’ll shoot.’

Clarity. Things coming back to today, to now. Vision.

He moved to the wall and stood there like a miscreant schoolchild.

‘Hands on the fucking wall. Now!’

He did as he was told.

‘Higher!

He moved his hands towards the ceiling.

‘Okay, son, frisk him for weapons. Move an inch, Deutch, and I’ll put a bullet in your fucking Kraut skull.’

The boy felt his raised arms, his shoulders, his sides and back, his legs.

‘He’s clean, Sarge.’

‘What the hell went on?’

‘I don’t know, Sarge. He came at me like he was trying to overpower me. I restrained him and called for help.’

‘Good boy. Okay, Mr. German Kraut. Twenty-four hours restricted food. Punishment for an escape bid. Water only.’

Wilhelm’s head was beginning to clear. He vaguely understood the punishment. Nowadays, he spoke sufficient American. And he smirked. As though increased starvation would affect his behaviour, or even alter his routine.

The three men left the cell and walked down the dank corridor before climbing the stairs to the subterranean chambers in which he would be interviewed by Broderick. It had been three days since he’d seen the light of day.

‘I was born when the century was already well under way … in 1911, to be precise, the same year as Dr. Josef Mengele.’

Broderick looked up from his notes. He’d heard the name Mengele, but couldn’t place him.

‘He was the chief doctor in Auschwitz. Indeed, I met him on many occasions in the mess hall. And I also saw him when I had to do work on Bloc 10 where they conducted medical experiments.’

‘I’ve heard of those. They were the subject of evidence of an earlier trial. Unspeakable.’

Wilhelm ignored his comments. ‘Mengele cut me dead when he saw me. Dead, so to speak. He was very arrogant and distant, considering me a mere maintenance man, although I was in charge of all the functions to do with the ovens and other things in the camp. Mengele went to university and got qualifications in philosophy and medicine. I never got past gymnasium … what you call high school. My parents were middle-class people, and had great expectations of me; they wanted me to go into a well-paying trade or even one of the professions, but I didn’t do well at school, and so reluctantly they put me into a mechanical trade.’

Broderick stood from his chair and massaged the small of his back. His testiness was increasing as the defense of the men he called beasts came to a conclusion in the courtroom above their heads, and it became increasingly obvious from the attitude of the judge that all the defendants would hang for crimes against humanity. ‘Look, Deutch, let’s cut to the chase.’

He paused for the translator to finish his work. He had now become used to the effect the translator had on the interview process. ‘This stuff about your birth and diapers and where you went to school is all very interesting, but it can be put down on paper and my assistant can make notes from it. I want to get down to business. I want to know how you came to be an engineer at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Did you resist your assignments? Did you refuse to obey orders because you knew in your heart that what you were doing was morally reprehensible …’

The translator looked up at him. ‘Reprehensible? I don’t know the German for that, sir.’

‘Try ‘unacceptable.’ He did. It worked.

Deutch shook his head. ‘I did what I was told to do. I have a wife and a daughter. To have refused to work in the East, in Poland, towards the end of the war, when Stalingrad had been lost and the German army was in full retreat, would have been unacceptable …’

‘But you weren’t in the army.’

‘We were all in the army. Even civilians. It was the great cause. Germany was stabbed in the back by the Jews and the Communists in the Great Patriotic War. For it to happen a second time was unthinkable. Even after Stalingrad our confidence in Hitler hardly wavered. Just as he did, we blamed it on the generals. The incompetents. But Göbbels made a brilliant speech, rousing us to even greater heights of patriotism. He explained why we’d lost. It was nothing to do with Hitler and the Nazis. It was the High Command which had miscalculated … and of course it was the Jewish financiers who had supplied the people of Stalingrad with sufficient food to hold out until the end of autumn, and just as Napoleon, the German army had been beaten by the savage Russian winter. Another Jewish conspiracy.

‘When our soldiers returned, bandaged and bloodied and in tatters, I couldn’t believe it. They’d marched out of cities in huge columns with tanks and armoured vehicles and whole armies of soldiers. So many soldiers we thought the columns of our men would never come to an end. How could they have lost?

‘I’ll tell you, when I saw them come back broken and stumbling, like the Freikorps wandered the streets after the Great Patriotic War in 1918, well, I hated the Jews so much. I could have strangled them with my bare hands. So when I was transferred from my job in maintenance at the IG Farben factory where I’d worked since I was a boy, and was told to take a troop train to work in a factory which I thought … which I was told … was in this small Polish town, I just went. I didn’t even think to question my instructions. We followed orders, even those of us who didn’t go to the army because we were in restricted professions in the homeland.’

‘Tell me about what happened when you got to Auschwitz,’ asked Broderick.

‘At first, I worked in Monowitz, which was the factory complex of Auschwitz. I. G. Farben was constructing the bigg

est synthetic rubber plant in the world, using the unending source of slave labour which Hitler and the German Army supplied to us.

‘That was only one of the factories in Auschwitz. God, how I wish I’d never heard the name. You know, we Germans call it Auschwitz, but in Polish, it’s Oswiecim. A difficult word to pronounce. We’d never heard of Auschwitz in Germany. It never came up in conversation. And we’d certainly never heard of Birkenau. It never occurred to me that Topf and Sons of Erfurt, a subsidiary of I. G. Farben, would have actually built the gas ovens on which I later worked. They were instructed to begin the building of the ovens in October, 1941, as I remember.’

Broderick looked up and frowned. He only knew the raw details, not the fine points of how Nazi Germany was organised. ‘Who ordered the construction of these gas ovens and crematoria?’

‘The orders came from Himmler himself. But he said they had to be built at Auschwitz. However, some time after the ovens were being manufactured, Heinz Kammler, the chief of Group C of the SS Economic-Administrative Main Office, arrived at Auschwitz on February 27, 1942 and ordered that the five-oven crematorium projected for Auschwitz be constructed at nearby Birkenau. Now you’d think that someone would be particularly brave to countermand one of Himmler’s instructions, but as Kammler was one of the closest associates of Himmler, no one dared disagree …’

Broderick shook his head in wonder as soon as the translator had finished.

‘You amaze me,’ he told the German prisoner. ‘You’re so accurate on detail. You’re so Teutonic in precision. And you applied yourself with the same meticulousness when it came to destroying an entire race of people. How do you know it was February, and October? I can’t even remember my wife’s birthday without writing it down, yet you can reel off names and places and dates and times as though you were a goddam adding machine.’

Birthright

Birthright The Pretender's Lady

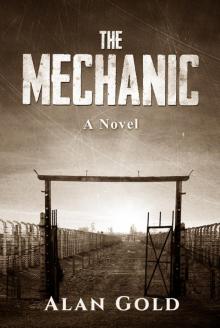

The Pretender's Lady The Mechanic

The Mechanic Bloodline

Bloodline Bell of the Desert

Bell of the Desert Bat out of Hell

Bat out of Hell Stateless

Stateless