Bell of the Desert Read online

Page 10

She heard a murmur of agreement from the dozens of princelings and other hangers-on lying on their divans, and immediately realized that she had just made a grave tactical error. Such errors in Arab society could prove deadly. Trying to recover, she said, “I have brought you gifts, Excellency, to show you my respect.”

“Are these gifts for me, or for my Emir ibn Rashid?” he asked. It was a trick question, and Gertrude knew she had to be wary of the answer.

“How two great men divide my king’s gifts is a question for the two great men, and not for me.”

He nodded, and asked her, “And have you brought the same gifts for the dog ibn Sa’ud?” he asked.

“It is not my custom to discuss what gifts I will give to him, just as I will never disclose what gifts I give to you and your Emir,” she said. She didn’t like the way the conversation was going.

Ibrahim continued to look at her for some time. She knew that by custom, an Arab woman had to avert her eyes when a man who wasn’t her husband looked at her; but she was damned if she was going to be cowed by the uncle of the Emir Rashid. She knew she had to stand up to him, or she’d be robbed of everything, and she and her men would probably be killed.

“You will be my guest until His Majesty the Emir ibn Rashid returns. He is in the north, fighting the Shammar. When he sits on his throne, he will allow you to leave.”

Suddenly frightened, she said, “But I have . . .”

“You have to leave here to visit Abdul Aziz ibn Sa’ud? No, you will stay until my Emir returns. Then we will decide what to do with you. Death, English, will be a merciful reward for those who seek to visit ibn Sa’ud. And your men beyond the gates will be treated to the hospitality of ibn Rashid.”

He grinned. She began to say she was given authority to be here by the Turks, but before she could utter a further word, Ibrahim rose from his throne, and walked to a rear entrance, leaving Gertrude standing there, alone and impotent, facing an empty chair. As he left, the dozens of princelings and other followers, scurried out after him until she was in the room with just three huge Nubian guards, who surrounded her, and led her to prison.

For every day of the two weeks she spent in the prison in Hayil, she dreamed of London—foggy, fussy, but delightfully safe London. She wondered what her friends were doing. Were they having dinner parties and discussing plays and concerts and things? As she sat in the roasting and airless heat of her cell, was anybody asking about her, she wondered? Would she ever again sit at a London dining table and regale politicians, writers, editors and her friends with her stories of Arabia, she wondered.

And what part would she now play in her grand plan to unify all of Arabia as a future great and modernizing nation when it allowed the sort of medieval barbarity she was experiencing, to exist? How could Arabia ever unite under a new Saladin when such primitive malevolence as she was suffering, was the norm? It had taken England hundreds of years to modernize from the cruelty of its kings to the emancipation of today. But the world couldn’t wait that long for Arabia to modernize. Its resources would soon be under siege, its people confronted with the prospect of freedom from serfdom, its women seeing life from the other side of the veil, and then all hell would break loose unless a strong leader held the nations together.

She could have accomplished so much! But now she’d have to wait for ibn Rashid to return and for the 16-year old to decide in a fit of childish pique whether to dispatch her and her men to their deaths. And if he did, would anybody in London know what had happened to her?

FOUR

London, 1914

The moment she saw it looming out of the London smog, her heart sank. It was a great moment in her life, yet the very building itself, supposed to define England’s solidity and permanency, was gloomy, melancholy, and fussy, a stolid construction of red bricks and chimneys and architraves. The feeling it imposed upon her as her carriage drew close was that of a building full of pomp and circumstance and self-importance, so very different to the ethereal, creamy, light-as-air architecture of Baghdad and Constantinople and the dozens of other cities of the Near East where she was truly happy.

The new headquarters of the Royal Geographical Society at Lowther Lodge in Kensington Gore overwhelmed the smaller houses beside it and diminished the charming park opposite in both stature and importance.

A shudder of despondency surged through her body as she stepped from her carriage and looked upwards to take in the enormity of its massive chimneys, its clumsy frontage and ridiculously delicate Queen Anne windows which were at odds with the ponderous weight of building. Despite herself, she couldn’t help but compare it to the delicate and deliciously ornate tents in which she lived when she explored Mesopotamia and traveled through the deserts of Arabia, or to the soaring gleaming monumental walls of Jerusalem, or the blinding white palaces of Damascus or Mecca or Medina which from afar looked like mirages of heaven. But that was an unfair comparison, because this was cold and gloomy England and the pure and breathless deserts were another time and another world away.

As she stepped onto the pavement, she shuddered at the thought of all those men who would be inside the building. All gathered there to celebrate her bravery, her adventures, and to congratulate her on achievements which no other woman had accomplished. Yet the setting was so very wrong. To properly appreciate what she’d achieved, this presentation should be made in a Sheik’s citadel in his desert domain, or some Caliph’s sandy kingdom or the Ottoman Sultan’s vast Topkapi Palace overlooking the Bosphorus in Constantinople, somewhere delicate and light and unearthly, something which looked like a wedding cake . . . not this red brick eyesore, a monument to the permanence of Rule Britannia.

Instead of driving through London’s parks with their stately poplars and elms and oaks, their tulips and daisies, she should be wandering amid palm fronds and date trees and fragrant orange groves, the air warm and sweet and heavy with the perfumes of frankincense and atar and roses and myrrh.

Rather than Londoners enshrouded in scarves and tweed coats and wraps to protect themselves from the unseasonably cold night air and ubiquitous smog, she should be walking amongst beautiful dusky women meandering through the shuks or the narrow ancient streets. And the men! Lean and tall and magnificent in their jet black beards, their faces burnished like bronze by the desert sun, walking majestically with leonine steps, supremely confident in their long galabiyahs, their swords and daggers swinging freely, their place in the world secure.

Unlike walking through the streets of London as merely another Englishwoman, she should be noticed and talked about, just as she was whenever she appeared in public in Arabia . . . glanced at covertly and in amazement by admiring Arabic women through the slits which showed only their eyes, or stared at in anger by the men because of her Paris outfits and because she dared to reveal her face and the shape of her body and look them confidently in the eye. Yes! That’s where she should be . . . in Arabia where she was able to be herself, and not a product of a society whose young men had rejected her.

She’d been back for three weeks, yet she couldn’t get London’s stench out of her nose. The city streets were piled high with rotting brown mounds of reeking horse dung around which unwashed people stepped with caution, its air laden with the fumes of coal fires and chimney smoke and soot and fog and the cloying stench of braziers burning coke to keep night watchmen warm or to enable hot chestnut sellers to ply their trade.

This was the London in which she’d spent much of her young adulthood, but since those days, the capital of Great Britain had become even more pestilential, as though Hell itself had opened its gates in London and emitted a sudden effluvium of fug from motorcar and omnibus exhausts. All the combined reek of coal and coke and dung couldn’t begin to equate to the choking pall of filth which hung at head-height as these new motorized vehicles belched their thick black smoke into pedestrian’s eyes and mouths. Blake’s green and pleasant land may exist beyond the borders of its capital city, but London was more Da

nte’s vision of Hell.

Hugh, her father, grasped her arm, and with his free hand, burrowed inside his cape to take some coins out of his purse to pay the driver.

“No need, m’lord. I’ve already been paid by the Royal Society. Thank you, m’lord, and I might I say, ma’am, that it’s been a privilege to have met you,” the cabbie said, and whipped the flanks of his horses which trotted off into the night, their iron shoes clattering over the cobblestones. Gertrude Bell looked at the carriage in astonishment. She hadn’t said a word to the cabbie since he’d picked her up at the hotel, yet he seemed to know about her. She immediately knew what was going through her father’s mind, when he whispered, “You’re something of a celebrity, dearest. Everybody’s talking about your exploits.”

Alone in the crowded London evening, Hugh put his arm around his marvellous daughter and whispered into her ear, “Look at the sign.”

She glanced towards the entrance foyer, and saw a billboard close to the street railings announcing the evening’s entertainment

Their Excellencies,

the Governors

and Hon. Members of the Committee

of the

Royal Geographical Society of Great Britain and Her Empire

proudly announce the granting of their prestigious Gold Medal

to

Miss Gertrude Bell.

Society Members Only. The public will not be admitted.

Involuntarily, Gertrude smiled. She was being recognised and rewarded for something which she had done merely because of her love for Arabia, for its archaeology and history, its isolation from the rest of the world, but especially for the ancient culture of the people. It was a great honour, but she wondered whether the Society would have awarded the Gold Medal had they known her real intention was not to explain Arabia as it was, but to change it to what it should be.

She drew closer to her father, and whispered into his ear, “It appears as if I’m a celebrity, father. This is all a bit strange.”

“You deserve being celebrated, my darling girl,” he said as they began to climb the steps. And as if to reassure her, he said, “they’ve all read your books. They know you were imprisoned by that bounder Rashid. We all know how hard it must have been for you, a woman, in a place like Arabia. They know . . .”

“Do they, father? I wonder . . .”

She thought back to her narrow escape just the previous year. She’d been isolated, terrified, threatened and for the first time in her life. Her will and resolve had nearly broken. Only when she herself had threatened that the British would send an army of a million men to rescue her had they begun to listen, as well as giving the Emir’s uncle her pair of Zeiss binoculars and a purse of gold.

Suddenly, as if on cue, the entire Board of Management of the Royal Geographical Society emerged to stand like a phalanx in the dusk and formed a line of honor in the entryway. They were enshrouded by the warm yellow light which flooded out the hallway, yet Gertrude could clearly see their faces. Each man was dressed in top hat, white silk scarf and tails, and looked very elegant. She immediately recognised the president, the Earl Curzon of Kedleston. Beside him stood Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich and to his left Sir Francis Younghusband.

Lord Curzon opened his arms in an embrace as Gertrude and her father walked through the gates and towards the entryway.

“My dear Gertrude. My dear girl. I can’t tell you how wonderful this is for all of us. It’s about time we recognised a woman. This is one of the proudest moments of my life.”

“Now George,” she said, chiding him gently, “I rely upon you to ensure this doesn’t all to go my head. I only did a bit of archaeology and exploration, nothing like your achievements.”

She embraced him, kissing him on both cheeks. The others bowed in mock reverence, as though she were royalty, and shook her hand as Lord Curzon introduced them in turn. Hugh basked in the esteem these brave men showed towards his daughter as Curzon introduced him to the Committee of Management. As he shook each man’s hand, he wondered how he, a simple industrialist, could have given birth to a girl as brilliant, adventurous, and extraordinary as his Gertrude.

They escorted her through the tiled vestibule of the Society with its red carpet, velvet curtains, and green leather furniture and into the large meeting hall, built like a tiered university lecture theatre, as imposing and awesome as any Greek amphitheatre of the ancient world.

As they walked in, five hundred members of the Society stood as one, and began their applause. The sudden rush of adulation made her breathless in a tide of apprehension and delight. Should she wave? Should she acknowledge their applause? Should she turn and bow?

Instead, she continued to walk in procession to the front of the lecture hall and out of the corner of her eye, she saw her father being shown to a reserved chair in the front row. She followed Lord Curzon and the others and sat in the centre of the raised dais in front of the lecture theatre. To be so honored by the Society was an explorer’s greatest accolade, and her presence in this room made her feel as though she was on hallowed ground. In the place she now occupied had stood some of the world’s greatest explorers, men such as Colonel Godwin-Austen, Sir Douglas Mawson, Commander Scott and the redoubtable Dr. David Livingstone. And now Gertrude Bell was to take her place before the assembly of the members of the Royal Society and receive the highest tribute which it could offer.

Lord Curzon banged his gravel on the oak desk and called for order. The members stopped their clapping and resumed their seats. Gertrude glanced at her father, and saw him trying to suppress his beaming smile.

“Gallant Lords, and most valiant members of the Royal Geographical Society. Tonight marks the beginning of a new era. Just over two decades ago, in 1892, Miss Isabella Bishop was elected as the first ever woman member of our Society. We have all read the remarkable exploits of Miss Alexandrine Tinné, the lady from Holland who first crossed the Sahara Desert in 1869. And who can forget Lady Stanhope who left the shores of England in 1810 to explore the unknown Middle East, never to return to her native land.

“But tonight’s recipient of the Society’s Gold Medal, Miss Gertrude Bell, is altogether of a different ilk. Indeed, it would not be an exaggeration to say that she stands proudly in a different league to all and any of the remarkable women who have gone before her. For unlike these other women, who were romantics and untutored in the ways of exploration, Miss Bell has defined her own category. The other women who indulged in some form of exploration, or were dabblers in adventure, had they been men, might have been called dilettantes, well-meaning amateurs setting out for their own vicarious pleasures. But not Miss Bell. Indeed, Miss Bell has crafted the mold for women for all time to come. She has broken barriers once thought impassable. She has crossed borders once thought impenetrable. She has set a standard to which other women, and indeed men, must now aspire.”

Gertrude couldn’t help herself, but looked up at George Curzon in bewilderment. Was he talking about her? Were these words about a woman who considered her own achievements as merely advancing knowledge of Arabia, and not much more? Were her achievements so vastly different to those of many of the men in this room? Would George, a most famous and celebrated politician and explorer himself, speak in this way about a male member of the Society? And if not, were her achievements of greater quantum merely because she was a woman?

Lord Curzon continued to define and expound upon Gertrude’s travels through Mesopotamia, her mapping and discovery of archaeological sites, the way in which she had created a demographic and cultural compendium of information about the previously unknown tribes of desert Arabs between the Tigris and the Euphrates in Mesopotamia, the dangers she’d faced, her recent imprisonment by an Arab bounder, and the fact that she had earned the unique title of Daughter of the Desert from patristic Arab chieftains and tribal leaders.

But Curzon didn’t merely outline her exploratory skills; he reminded them that she had enjoyed an outstanding academic career at Oxford Univer

sity, that she had written the most brilliant and well-received books about her travels, which had the reviewer for The Times waxing emotionally about her literary skills. He also told the members how she’d given vital intelligence to the British government about how England could benefit in Arabia from the downfall of the Ottoman Empire, a crumbling nepotistic and diseased empire which was on the verge of collapse.

Curzon even conspired to talk about Gertrude’s mountaineering adventures and there was a further round of applause when he told the audience she’d taken up the challenge published in The Times and that previously unconquered peaks and passes in the Swiss Alps had been named after her.

And he finished with a particularly generous rhetorical flourish, when he said, “Gentlemen, had I been speaking of one of our sex, I am in no doubt that you would rise to your feet and carry this brave member shoulder-high into the dining room. But I speak not of a man, but of a woman . . . a very attractive woman . . . a woman of great intellect whose first class degree in history from Oxford university was earned in a mere two years, the first time such a feat has ever been accomplished.

“My lords, Honored Members, and Gentlemen, I have the utmost pleasure and great privilege of presenting the Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society to Miss Gertrude Lowthian Bell.”

The applause resumed, this time with a thunderous stamping of feet. Everyone had known Gertrude Bell as a woman of splendid achievement, but none, other than her father and her friend George Curzon, knew of the extent of her extraordinary life. At the age of forty-six, she had achieved what most men could only have achieved in a dozen lifetimes.

She stood to receive the Gold Medal, proffered by Lord Curzon, who had arranged for it to be ribboned so he wouldn’t embarrass her by having to pin it onto the bodice of her gown. She wore it as she walked the few steps to the lectern, and waited for the deafening applause to die down. She knew some of the faces in the crowd personally, others she recognised from engravings in The Times. She wondered how many would be invited to the special dinner in her honor that night.

Birthright

Birthright The Pretender's Lady

The Pretender's Lady The Mechanic

The Mechanic Bloodline

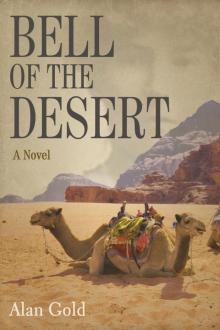

Bloodline Bell of the Desert

Bell of the Desert Bat out of Hell

Bat out of Hell Stateless

Stateless